Truc

Truc is a trick-taking game played throughout Spain and southern France. It is played by four players in partnerships. Unlike most trick-taking games, Truc doesn’t require you to follow the suit of the card led. Hands of Truc can be very short, because they are only played out until a majority of the three tricks have been decided. A hand of Truc can also be abruptly stopped by one team rejecting a proposed raise by their opponents.

Truc is descended from Put, a game played in England as far back as 1674. Truc, in turn, was exported to South America, where it evolved into Truco.

Object of Truc

The object of Truc is to be the first partnership to score twelve points by taking at least two of the three tricks in each hand.

Setup

Truc is traditionally played with a Spanish 40-card deck. To make an equivalent deck out of a standard 52-card deck of Denexa 100% Plastic Playing Cards, remove the 8s, 9s, and 10s, leaving a deck of aces, face cards, and 7s through 2s in each of the four suits. You also need some way of keeping score, such as pencil and paper.

Determine partnerships by any method that is agreed upon, such as a random method like high-card draw or simply mutual agreement. Players sit opposite one another. Prior to the first hand, each partnership may retreat to a location where the other team will not overhear them and devise a system of signals to use throughout the game. These signals can communicate anything that the players desire, including the overall strength of their hand, the cards they hold, what they want their partner to play, and so on. Partners can also communicate verbally throughout the hand. Nothing’s off limits!

The dealer shuffles and offers the deck to the player to their left to cut. They may do so, or simply tap the pack, declining to cut. If the deck is cut, deal three cards to each player. If the cut was refused, the dealer has the option to deal only one card to each player (making for a much shorter hand).

Card ranking

Truc uses a special card ranking unique to the game. 3s, 2s, and aces are the highest-ranking cards in the game, and the rest of the cards rank in their usual order. Therefore, the full rank of cards is (high) 3, 2, A, K, Q, J, 7, 6, 5, 4 (low).

Game play

Game play starts with the player on the right of the dealer, and thereafter continues to the right. This player leads to the first trick. Each player in turn plays a card to the trick. A player may play any card to a trick; there is no requirement to follow suit. The person playing the highest card wins the trick. If two players on opposite teams tie for high card, the trick is a draw. The individual player that won the trick leads to the next one. If nobody won the trick, the player who led to that trick leads to the next one.

A hand only continues until the majority of tricks in it have been determined. If the first two tricks are won by the same partnership, there is no need to play the third one.

The partnership that wins the majority of the tricks wins the hand. If there is a tie, due to one or more tricks not being won by either player, the dealer’s opponents win the hand. Whichever team wins the hand scores one point. The deal passes to the right, with any unplayed cards shuffled into the deck unexposed.

Raising the stakes

At any time during their turn, either before or after playing a card, a player may raise the stakes for the hand to two points by calling “truc”. The next player in turn may either accept the raise by playing a card (or making a verbal declaration of “accept”, “OK”, or the like) or reject it by placing their cards face down on the table (or saying “No” or similar).

Once a truc has been accepted, it may be re-raised by calling “retruc”, proposing a raise to three points. As before, the next player to their right then has the option to accept or reject the retruc. Only an opponent of the first raiser may re-raise. A retruc may be called either on the same trick as the original truc, or a later trick.

If a raise is accepted, the winners of the hand score the amount of points agreed to as a result of the raise. If a raise is rejected, play of the hand stops immediately. The partnership that proposed the most recent raise scores whatever the last agreed-upon amount for the hand was.

A score of eleven

Because a partnership with a score of eleven is only one point away from winning the game, special rules apply when either partnership has scored eleven points. A full three-card hand must be dealt; a player cannot give the dealer the option to deal only one card. If only one partnership has a score of eleven, that partnership looks at their cards and decides whether or not to play. If they do, the hand is played for three points. In the event that both partnerships are tied at eleven, the hand is played as usual, with the winner of the hand winning the entire game.

The first partnership to score twelve or more points is the winner.

Schwimmen

Schwimmen, also known as Thirty-One (no relation to the other game called Thirty-One that we’ve covered), is a member of the Commerce family of card games. It can be played with two to eight players. As with other games in that group, the game revolves around exchanging cards from your hand with cards on the table. Though known worldwide, it is most popular in Germany and western Austria.

Schwimmen, also known as Thirty-One (no relation to the other game called Thirty-One that we’ve covered), is a member of the Commerce family of card games. It can be played with two to eight players. As with other games in that group, the game revolves around exchanging cards from your hand with cards on the table. Though known worldwide, it is most popular in Germany and western Austria.

Object of Schwimmen

The object of Schwimmen is to form the hand with the highest point value by exchanging cards from the table with those from your hand.

Setup

Schwimmen uses the 32-card deck common to many German games. Starting from a standard 52-card deck of Denexa 100% Plastic Playing Cards, remove the 2s through 6s, leaving 7s through aces in each of the four suits. Score is kept using tokens, such as chips. Give each player an equal number—three works well.

Shuffle and deal each player three cards. Then deal three cards, face down, to the center of the table. The remainder of the deck becomes the stock.

Game play

Aces are worth eleven points, face cards are worth ten, and all others their face value. Suits rank (high) clubs, spades, hearts, diamonds (low), the same order as in Skat.

Prior to the start of actual play, the dealer looks at their hand and decides whether they want to keep it. If they do, the cards on the table are simply flipped face-up. If not, the dealer discards their original hand, takes the three face-down table cards as their hand, then turns their old hand face up on the table.

Play of the hand

The player to the dealer’s left goes first. On their turn, a player may exchange one card from their hand with one on the table. If a player greatly dislikes their hand, they may elect to exchange all three cards. It is not allowed to keep one card and exchange the other two, however; it’s one or all. A player may also pass if they do not like any of the cards on the board.

The turn then passes to the left. This continues until one player is satisfied with the value of their hand. They then close the hand (equivalent to knocking in many other card games). Each of the closer’s opponents gets one last turn, and the hand ends when the turn to play again reaches the closer.

If an entire orbit around the table is made with every player passing, the dealer discards the three board cards. They then deal three new board cards from the stock.

Special combinations

There are two special combinations in Schwimmen:

- Feuer: Three aces. Such a hand is worth 32 points. (Feuer is German for fire.)

- Schnauz: A hand, all in the same suit, with a value of exactly 31 points. This can only be achieved by holding an ace and two of the ten-point cards (the face cards and the 10).

When a player finds themselves with a special combination, whether because it was dealt to them or because they exchanged to get it, they must reveal it immediately. The hand ends at that point. (Because the hand was not closed, the other players do not get another turn.)

Scoring

After a hand ends, each player calculates their score. The hand score, in most cases, is the value of all of the cards of its highest-scoring suit. For example, a hand of A♠-K♦-7♥ would score eleven. This is because the player holds three one-card suits, and the spade is the highest-scoring. However, a hand composed of A♠-K♦-7♦ would score seventeen, because the diamonds combine to outscore the lone spade.

There are a few exceptions to this scoring method. Two of these are the special combinations described above. A third is that three-of-a-kind always scores 30½, no matter what rank it is.

If a player wins with a Feuer, then each of their opponents loses one chip. Otherwise, just the player holding the lowest point total loses one chip. If there is a tie for lowest, it is broken by the suit of the player’s scoring cards. Ranks of three-of-a-kinds are broken by the rank of the three-of-a-kind. If there is still an unresolved tie, then both players lose a chip.

Ending the game

The deal passes to the left, and another hand is played. Players will continue losing chips as further hands are played. When a player loses all of their chips, they are said to be schwimmen (German for swimming). A schwimmen player can continue playing, but if they lose again, they are eliminated.

Game play continues until all of the players but one are eliminated. The sole remaining player is the winner. (If the last two players are tied on a hand while they are both schwimmen, play another hand as a tiebreaker.)

See also

Indian Chief

Indian Chief is a unique rummy game for two to eight players. It bears a slight similarity to the Contract Rummy subfamily of games, due to its requirement to form a particular series of melds. Unlike the Contract Rummy games, however, the order that the melds are formed doesn’t matter, so long as the cards melded can be counted as something. In this way, the game is more akin to the dice game Yacht than many card games!

Indian Chief was created by Stven Carlberg of Decatur, Georgia. He posted its rules to the BoardGameGeek forum in January 2009. The game was very well received there; several players created additional scoresheets and reference materials for it. It continues to be actively recommended by the site’s userbase to this day.

Object of Indian Chief

The object of Indian Chief is to form the highest-scoring instances of the game’s seven melds.

Setup

Indian Chief uses one standard 52-card deck of playing cards, when playing with two or three players, and two standard decks if you’re playing with more than that. If you’ve got some Denexa 100% Plastic Playing Cards handy, why not use those?

Indian Chief uses one standard 52-card deck of playing cards, when playing with two or three players, and two standard decks if you’re playing with more than that. If you’ve got some Denexa 100% Plastic Playing Cards handy, why not use those?

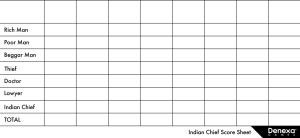

You also need a Indian Chief score sheet and something to write with. If you want, you can print off ours (shown to the right; click on it to bring it up full-size). Otherwise, just copy it down onto whatever sort of paper is handy. Most people will use something like a piece of notebook paper, but if you want to scribble it down on the back of a junk mail envelope, well, you do you.

Shuffle and deal eight cards, face down, to each player. Set the deck stub aside.

Game play

Players look at their hands and decide on which meld they wish to form. They take the cards forming that meld from their hand and, at a signal, all players reveal their melds simultaneously. The value of each player’s meld is calculated and recorded in the appropriate box on the score sheet under their name.

Players do not have the option to simply not meld—a player must make a meld on every turn. Because each meld includes a different number of cards, it is obvious which meld a player is attempting to make by the number of cards they reveal. If the revealed cards don’t qualify for the meld attempted, the player simply enters a score of zero in that box. Players may not attempt to re-make a meld that they already have a score written down for (e.g. if you already have a number in the “Doctor” box, you cannot make another six-card Doctor meld).

Once the melds have been scored, the dealer replenishes everyone’s hands back up to eight cards from the deck stub. The melds from the previous round are then collected and restored to the deck. The deck is then shuffled in preparation for the next turn.

The melds

Below are the seven possible melds (each named after a line in a Mother Goose rhyme) in Indian Chief. When a card’s “face value” is referred to, aces are worth one point, face cards are worth ten points, and all other cards their pip value. The number next to each meld is the number of cards it contains.

- Rich Man (5): Any five cards. The face values of these five cards are added together and placed on the score sheet as a negative value.

- Poor Man (3): Any three cards. The face values of any spades melded are added together to determine the score for the meld.

- Beggar Man (2): Any two cards. Score two points for each of the cards in the opponent’s melds that match the Beggar Man cards in rank.

- Thief (1): Any one card. Score its face value. After the melds have been scored, a player melding the Thief may steal a card from an opponent’s meld instead of being dealt an unknown card from the deck. If multiple Thieves have been played on one turn, they steal in order from the lowest card played to the highest. If there’s a tie, they must agree to steal different cards, or neither of them may steal.

- Doctor (6): Six cards of all different ranks, one of which must be a heart, and one of which must be an ace. If all conditions are met, the player names a suit and scores ten point for each of the cards in the meld of that suit. Otherwise, score zero.

- Lawyer (4): Four cards whose face values add up to exactly 25. If they do, score 25 points; otherwise, score zero.

- Indian Chief (7): A five-card poker hand (see rank of poker hands) and a two-card Baccarat hand. Score the Baccarat hand first, by adding the values of the two cards, then dropping the tens digit. Add the value of the poker hand, as listed below, to get the total score for the meld:

- Five of a kind: 50 points.

- Straight flush (including royal flushes): 45 points.

- Four of a kind: 40 points.

- Full house: 35 points.

- Flush: 30 points.

- Straight: 25 points.

- Three of a kind: 20 points.

- Two pair: 15 points.

- Pair: 10 points.

- High card: 5 points.

Ending the game

The game ends after seven turns, after which each player will have filled up their score sheet. The players’ scores for each meld are simply totaled, and the player with the highest score wins.

External link

- Original post at BoardGameGeek (includes an explanation of how the melds relate to their names)

Nuts (a.k.a. Nerts, Pounce)

Nuts, also known as Nerts, Pounce, and Racing Demon, among other names, is a competitive solitaire game. It can be played by two to four players, although more may be accommodated by dividing into partnerships. Functionally, Nuts resembles multiple frenzied games of Canfield being played simultaneously.

Object of Nuts

The object of Nuts is to achieve the highest score by moving as many cards out of your reserve as possible and by moving cards to the foundations.

Setup

To play Nuts, you’ll need one deck of cards for each player. Each deck of cards in play must have a distinct back design. The frenzied pace of Nuts means cards can get bent up and damaged pretty easily. With a sturdy deck of Denexa 100% Plastic Playing Cards, you’re far less likely to have to stop the game and hunt for a replacement deck. Plus, they come in a two-deck set, which is perfect for a two-player game of Nuts.

You’ll also need something to keep score with, such as the venerable pencil and paper.

Players should seat themselves such that they are all facing a central area, where the foundations will be played. This central area should be accessible by all players, with plenty of room between players to allow for easy movement. If playing with an even number of players greater than four, players should pair up by any convenient means. Partners should sit next to one another. In a partnership game, the partners cooperate, however they see fit, to play more quickly. (We will describe the game as though it were being played by solo players below; any time a “player” is mentioned it should be understood that this applies to a partnership, where appropriate.)

Each player shuffles and deals thirteen cards from their own deck, face down, into a pile. They then square up the pile, and turn it face up, so only the top card can be seen. This forms the reserve. To the right of the reserve, deal a line of four cards, face up, forming the tableau. The remainder of the deck becomes the stock.

Game play

There are no turns in Nuts. Instead, everyone plays simultaneously. When conflicts arise, the first card to be played (usually the one that ended up below the other) takes precedence. Cards rank in their usual order, with aces low.

Play of the hand

The tableau is built down by alternating colors (red cards are played on black cards and vice versa), in descending rank order. When a card is moved, all cards on top of it are moved as well. In other words, the tableau works pretty much exactly like that of Canfield or Klondike. A player may play to their own tableau only; their opponents’ are off-limits.

The top card of the reserve is available to be moved to any legal location at any time. Cards beneath the top card are not accessible and should not be known to the player.

Cards may be drawn, three at a time, from the stock and placed in a discard pile, from which they may be moved to any location. Only the third card is available for play, freeing up the second card when the third is played, etc. After the stock is fully depleted, the discard pile is flipped over to replenish it.

When an empty spot appears in the tableau, any accessible card (the top card of the reserve, a card from the discard pile, or cards from elsewhere in the tableau) may be moved to fill the vacancy.

When a player encounters an ace, it may be moved to the central area to form a new foundation pile. The foundation piles are built up by suit, in ascending rank order. Any player may add to a foundation pile, not just the player that started it. Players may create a new foundation whenever they have an ace, even if another incomplete foundation pile exists. No new cards may be added to a foundation whenever a king has been played to it. Once played to a foundation, a card cannot be removed from it.

Getting stuck

After the hand has gone on for a while, players will be unable to make any additional moves, due to a lack of necessary cards (trapped either in the reserve or in inaccessible parts of the stock). When all players reach this state, or otherwise agree to do so, they may flip their discard piles to reform their stock, then, move its top card to the bottom. This is usually enough to adjust the deck so new cards are now accessible.

Ending the hand

The hand ends whenever a player depletes their reserve. They call out “Nuts!” and game play immediately ceases. (Players in the process of moving cards may complete their moves, but no new cards may be picked up.)

It occasionally happens that none of the cards in a player’s stock are playable. If every player finds themselves in this situation, the hand ends.

Scoring

The foundation piles are collected, then separated based on their backs. This allows a count to be made of the number of cards each player contributed to the foundations. Each player scores one point for each card played to the foundations. Two points are then subtracted for each card left in their reserve.

Players collect their cards back into full decks, then shuffle and deal new hands. Game play continues until at least one player exceeds a score of 100 points. The player with the highest score at that point is the winner.

Bridgette

Bridgette is a two-player adaptation of Contract Bridge. The game makes up for the loss of complexity caused by only two cards being played to a trick with the addition of three special cards known as “colons”.

Bridgette was invented in 1960 by Joli Quentin Kansil. Kansil is an game inventor and author, having published 36 games over the course of his lifetime. Of these, Bridgette is the most well-known. Kansil’s company produces a proprietary version of the game including the extra cards, as well as a number of additional props.

Object of Bridgette

The object of Bridgette is to accurately predict the number of tricks in excess of six that you will be able to win.

Setup

Bridgette is played with a 55-card deck formed by adding three distinguishable jokers or other extra cards to the deck. These cards serve as the Grand Colon, the Royal Colon, and the Little Colon. If you’re using a deck of Denexa 100% Plastic Playing Cards, the red joker (the one with the dragon) can be the Grand Colon, the black joker (the one with the jester) the Royal Colon, and the Guarantee card (the card with the teal G as the index) can be the Little Colon.

You also need something to keep score with. Compared to full Contract Bridge, Bridgette’s scoring is considerably simplified, and therefore a Bridge scoresheet is not necessary. A simple piece of paper and a pencil will do, or a smartphone, or whatever sort of more elaborate contraption you can come up with.

Shuffle and deal thirteen cards to each player. Next, place the stub in the center of the table, forming the stock. Then, turn the top card of the stock face up. This card is the upcard.

Game play

Cards rank in their usual order, with aces high. The colons are not considered to rank relative to the other cards. (See below for a description of the colons and their use.)

The exchange

A hand of Bridgette begins with the exchange. This allows the players to receive more cards and discard the weaker ones from their hand. The non-dealer first takes the top two cards of the stock. The number of cards the dealer may exchange is governed by the upcard. If the upcard is a 2–10 or the Little Colon, the dealer draws four cards. With an upcard of a face card or the Royal Colon, the dealer draws eight cards. If the upcard is an ace or the Grand Colon, the dealer draws twelve cards. After drawing, both players discard back down to thirteen cards.

Bidding

The next phase of the hand is bidding. Bids consist of a number, representing the number of odd tricks (tricks in excess of six) that the player will collect during the course of the hand, and either a suit to become trump for the upcoming hand or “no trump”. From lowest to highest, the suits rank clubs, diamonds, hearts, spades, no trump. Unlike in Contract Bridge, in Bridgette, the lowest possible bid is 0NT, which is a bid to take six tricks with no trump. The next highest bid is 1♣ (the lowest bid in Contract Bridge), a bid to take seven tricks with clubs as trump. 1♣ would be overcalled by a bid of 1♦, and so on up to 1♠, then 1NT, which would be overcalled by 2♣.

Bids in Bridgette are subject to certain restrictions. A player must have at least two cards in a suit to bid with that suit as trump. A player must have cards in all four suits in order to bid no trump. Also, in order to make a jump bid, a bid higher than necessary to overcall the previous bid, a player must have four cards of the suit bid.

The dealer must make the opening bid. Thereafter, the non-dealer may choose to bid higher or pass. Bidding continues until there are two consecutive passes. That is, if one player passes, the other may continue raising the bid, if desired (subject to the above restrictions).

A player may also double the bid. Doing so keeps the bid the same, but increases the risk and reward of completing the contract. When a bid is doubled, the opponent may make a higher bid, end the bidding immediately by passing, or redouble the bid. Redoubling the bid further increases the risk or reward of the contract and immediately ends the bidding.

When the bidding is completed, the high bidder becomes the declarer for the hand, and their opponent becomes the defender. The declarer’s bid becomes their contract for the hand.

Play of the hand

The declarer leads to the first trick. Players must follow suit if possible; if they cannot, they may play any card, including a trump. Tricks are won by the player who played the highest card of the suit led, or if the trick contains a trump, the highest trump. When a player wins a trick, they place the card they played to it face down to the left of them. When they lose, they place the card face down to the right. The player who wins the trick leads to the next one.

Using the colons

The colons have special rules for when they can be played and when they can win a trick. Each colon represents a portion of the pack. The Grand Colon corresponds to the aces, the Royal Colon to the face cards, and the Little Colon to the 2s–10s.

A player may play a colon to a trick that they didn’t lead, so long as the lead falls into the colon’s range. The colon loses the trick, but the player leading to the next trick must play a card of a different suit than that they just led.

Players may also lead colons, to which the other player may play any card they wish. If the other player responds with a trump or a card falling into the colon’s range, the colon loses the trick. If they instead respond with a non-trump outside the range of the colon, the colon wins the trick.

Scoring

After thirteen tricks have been played, the declarer counts the number of tricks they took. If it is equal to or greater than the number of tricks specified by their contract, they have made their contract. If it is less, they have broken their contract or been set.

When the declarer makes the contract

If the declarer makes their contract, they score according to their bid:

- 0NT, 1♣♦♥♠: 150 points

- 1NT, 2♣♦♥♠, 2NT, 3♣♦♥♠, 4♣♦: 250 points

- 3NT, 4♥♠, 4NT, 5♣♦♥♠: 750 points

- 5NT, 6♣♦♥♠: 1500 points (a small slam)

- 6NT, 7♣♦♥♠: 2200 points (a grand slam)

- 7NT: 2500 points (a super slam)

Successful declarers may also score the following bonuses:

- Exacto bonus: For bidding the exact number of tricks taken. For bids between 0NT and 5NT, this is worth 250 points; for bids of 6♣♦♥♠ or 6NT, it is worth only 100 points. No exacto bonus is available for bids greater than 6NT.

- Trifecta bonus: For capturing exactly three overtricks. 350 points. (No overtrick bonus is awarded for any amount other than three overtricks.)

- For fulfilling a doubled contract: 400 points.

- For fulfilling a redoubled contract: 1000 points.

When the declarer is set

When the declarer does not make their contract, they score nothing. Instead, the defender scores based on the declarer’s trick deficit:

| Tricks down | Undoubled | Doubled | Redoubled |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 100 | 200 | 300 |

| 2 | 200 | 500 | 700 |

| 3 | 300 | 800 | 1100 |

| 4 | 400 | 1100 | 1500 |

| 5 | 700 | 2000 | 2700 |

| 6 or more | 1000 | 3000 | 4000 |

Ending the game

The deal passes to the non-dealer on the first hand. Game play continues until six hands have been dealt. Whichever player has the higher score after the sixth hand is the winner. If scores are tied, play a seventh hand to break the tie.

Tadmur

Tadmur is a card game for two players. Its creator describes it as “about 40% chance and 60% bluffing”. In Tadmur, players try to create a chain of cards leading between two other cards, while keeping their eventual target a secret.

Tadmur was submitted to Reddit by user BarryAndAGrande in September 2016. The user described the game of having been devised during an evening in Tadmur (Palmyra), Syria. Due to a lack of TV or any other entertainment other than a deck of cards, they devised the game of Tadmur to pass the time.

Object of Tadmur

The object of Tadmur is to either be the first player to complete a chain of consecutive cards, or to guess the ending card of your opponent’s chain before they complete their chain or guess your ending card.

Setup

Tadmur uses one standard 52-card deck of playing cards. If you’ve got a deck of Denexa 100% Plastic Playing Cards handy, go ahead and use those. (If you don’t, why not?)

Shuffle and deal two cards face up in a vertical column to one end of the table. These two cards are the starters (one for each player). Deal two cards, face down, to another vertical column, approximately seven card widths from the starters. (It may be helpful to use face-down cards from another deck to delineate these empty columns.) These two cards are the players’ target cards. Each player may look at their target card, but must keep them concealed from their opponent. Deal the rest of the pack out as the two players’ hands (24 cards each).

Game play

The non-dealer goes first. They play a card of one rank higher or one rank lower than the starter to the next empty space after it. Cards rank in their usual order, with aces being consecutive to both 2s and kings (so Q-K-A-2 is a valid sequence). After playing a card, the dealer may do the same. On the non-dealer’s next turn, they play a card consecutive with the card they played on the last turn, placing it next to that card, and so on, building a chain of cards toward their target card.

As the game goes on, a player may start to get an idea of their opponent’s target card, based on the cards on the board and in their hand. Prior to playing a card, a player may guess the rank of their opponent’s target card. If they are correct, the opponent reveals the card and the game is over, with the guesser winning. If they are wrong, the guesser moves their target card one space further away from their starter. They then play a card as per usual, and the game continues. A player may only make one guess per turn. A player may not make a guess when a player is only one turn away from completing their chain.

Players do not necessarily have to make a chain with the lowest possible number of cards. For one thing, a successful chain will be at least nine cards long (i.e. seven cards must be played to link the starter and the target). Players may find it in their best interest to obfuscate the path from point A to point B by playing cards in a meandering sequence, going up and down, to try to prevent their opponent from guessing. Players may even make random guesses to rule out one of the thirteen possibilities, or to intentionally increase the length of the chain to provide more space to mislead their opponent.

The game ends when:

- A player successfully guesses their opponent’s target card. The guesser wins the game.

- A player forms a successful chain of sequential cards from their starter to their target card, filling all of the blank spaces between the two. That player wins the game.

- A player runs out of cards without fulfilling either of the above two conditions. Their opponent wins the game.

External link

Bridge Solitaire

Bridge Solitaire is a one-player variant of Contract Bridge invented by Stephen Rogers. In Bridge Solitaire, a player follows the typical flow of a Bridge hand, from bidding through play of the hand. The undealt cards in the deck serve as the player’s “opponent”.

Rogers shared the game with us at our Card Game Night event here in Norman in December 2016. It borrows some play mechanics from Natty Bumppo’s Euchre Solitaire game, published on John McLeod’s Pagat.com. Rogers created the game as a response to the difficulties finding three other willing participants for a true Bridge game. He bestowed the game with an alternate title, You People Suck, in reference to those who would rather spend time on their phones than play a game of Bridge!

Object of Bridge Solitaire

The object of Bridge Solitaire is score as many points as possible playing a game of Contract Bridge against the deck stub. Points are scored by accurately predicting the number of tricks in excess of six that you will be able to win. The ultimate goal is to thus win two games, which constitute a rubber.

Setup

Bridge Solitaire uses the same standard 52-card pack that Contract Bridge uses, plus two jokers. We’re not certain if Bridge Solitaire was invented with a pack of Denexa 100% Plastic Playing Cards. We’re pretty sure they’re the cards the game is most frequently played with, though!

You also need a typical Bridge scoring sheet. Pre-printed ones exist; they’re ruled into four quadrants, the columns headed by ‘WE’ and ‘THEY’. If a pre-printed scoresheet isn’t handy, you can easily make one by simply dividing a sheet of paper with a vertical and a horizontal line. (‘WE’ and ‘THEY’ seem a little pretentious if you’re playing solitaire, though. ‘ME’ and ‘IT’ are probably more appropriate, or ‘PLAYER’ and ‘HOUSE’ if you feel like being more serious about it.)

Shuffle and deal seven cards face down without looking at them. Then, deal thirteen cards face up in front of you. The deck stub becomes the stock, which will serve as the player’s opponent for the rest of the hand. For the sake of clarity, we’ll refer to the theoretical player the deck is representing as the house.

Game play

Cards rank in their usual order, with aces high. The jokers (★) do not have any rank and cannot win or lose a trick.

Determining the player’s hand

The player begins by choosing their hand. The seven face-down cards will be part of their hand no matter what, and they cannot change any of these cards. Before looking at them, though, they do get to choose the other six cards in their hand from the thirteen face-up cards available to them. If there are any jokers in these thirteen cards, the player is obliged to take them. Otherwise, the player is free to select cards however they see fit.

The unchosen cards are discarded in a face-up discard pile, and the face-down cards are turned up. The chosen cards are added to these previously-unknown cards, allowing the player to see their full thirteen-card hand. The discarded cards (save for the top card of the discard pile) cannot be inspected after this point; if a player wishes to use information from them, they must commit it to memory.

Bidding

After the hand has been determined, the play proceeds to bidding. Bids function the same as they do in Contract Bridge. Each bid consists of a number of odd tricks (tricks in excess of six) that the player is committing to take. This is combined with a suit that the player is proposing to make trump, or “no trump”. From lowest to highest, the suits rank clubs, diamonds, hearts, spades, no trump. Therefore, the lowest bid is 1♣, which would be overcalled by a bid of 1♦, and so on up to 1♠, then 1NT, which would be overcalled by 2♣.

The house always bids first; its bid is determined by the contents of your hand. The house will bid the suit that the player has the least cards in. The numerical content of the bid is calculated by examining each suit and counting the number of “winning tricks” the player can make. For example, in diamonds, the player has A-Q-10-9. The A♦ would win a trick (being the highest diamond), the 9♦ would lose to the K♦ (which is held by the house), the Q♦ then wins a trick (being the highest unaccounted-for diamond), and the J♦ would take 10♦, so the player has two winning tricks in diamonds. The sum of the values from each of the four suits is subtracted from six. If the result is zero or negative, the house passes. Otherwise, the resulting value (combined with the player’s short suit) is the house’s bid.

No Trump bids may only be made when the player holds one of the following suit distributions: 4-3-3-3, 3-3-3-3-★, 3-3-3-2-★-★.

If the house passes, the player is required to make a bid. Otherwise, the player has the option to overcall the house and play as declarer. They may also pass, and play as defender.

If the player holds one joker, the contract is doubled. If holding two jokers, it is redoubled.

Play of the hand

The play of the hand is conducted according to the usual Bridge rules. Both the player and the house must follow suit if possible. If the player is unable to follow suit, they may play any card. The highest played card of the suit led wins the trick, unless a trump was played. In that case, the highest trump wins.

Whichever player is defending leads to the first trick. When the house leads, it does so by simply playing the top card of the stock. If the player leads, cards are turned over from the stock until a card that can be legally played is exposed. The trick is then placed in one of two discard piles (one for the player and one for the house), face down. Since it is important to keep track of the number of tricks captured, it may be helpful to place each trick onto the pile at right angles. This allows the tricks to be easily separated after the hand. The player that won the trick leads to the next one.

A special rule applies during No Trump contracts. When the player leads, the house may play a maximum of only four cards from the stock. If, by the fourth card, the house has not made a legal play, the player wins the trick by default. They then lead to the next one, as usual.

Jokers have a special role in the game. If the player cannot follow suit, they may respond with a joker instead of playing any other card. If the house leads a joker, the player may play any card they wish. The house wins any trick containing a joker, with one exception. Should the player respond to a joker led by the house with the other joker, the player wins the trick instead. (A player may presumably lead a trick with a joker as well. There seems to be little point in doing so, however.)

The hand ends when thirteen tricks have been played, meaning that the player has run through their entire hand. In the event that the stock is exhausted before the hand is completed, the last card of the stock is the house’s play for the last trick. Each remaining card in the player’s hand is considered a trick won by the player.

Scoring

Scoring is done according to typical Contract Bridge scoring rules.

Example hands

The following hands, and the accompanying commentary, were given to us by Rogers to help illustrate the game:

Example 1

After shuffling, a player deals out seven face-down cards face down into a pile, and then thirteen cards face-up, setting the rest of the deck aside to form the stock. The thirteen face-up cards look like this: J-10-7-2♠, 9♦, A-K-10-8♣, Q-8-5-4♥.

The player, not particularly thrilled with this draw, begins weighing their options of which cards to keep. The 9♦ is an obvious throwaway, while A-K♣ will automatically give them two winning tricks against the stock. Taking Q-8-5♥ would also guarantee a third trick in hearts, but taking half the potential draw for a single trick seems unwise, and going J-10-7-2♠ for a single trick in spades is right out. The player ultimately selects A-K-10-8♣, Q-8♥, throwing out the other face-up cards into a face-up discard pile with the J♠ on top, a reminder that they threw away one of the honors in that major suit. This gives them two tricks for sure and a potential third if the face down cards include at least one lower-ranked heart.

The player then picks up the seven face-down cards and, having looked them over, happily adds them to their hand—the final disposition of their hand is: A-K-Q-J-10-8♣, Q-8-7♥, 9-4♠, 3♦, ★.

Next, they need to evaluate their hand for the deck bid—here it’s an easy thing to determine. With five honors in clubs, they have five winning tricks in that suit. They were also given another heart, so the queen is good for a trick there. Diamonds and spades are duds, but it doesn’t matter—the player has six tricks in hand, so the deck will pass. The player decides to play conservatively since they have two suits without stoppers in them, and bids 1♣. Thanks to the joker in their hand, the final bid is 1♣ Doubled.

Since the player bid to play, a card is dealt off the top of the stock, in this case the 3♣, which the player counters with 8♣, winning the first trick. The player then leads the A♣ and draws the next card off the stock, which is the 7♦. Since this is neither a trump nor a card of the suit led, it is ignored and another card is dealt, the 5♦. This is also invalid—the A♥ is turned up (something of which the player takes note) before the deck finally yields up 9♣, a valid play. Player wins the second trick.

The player plays their next three trump honors in sequence, forcing the deck to cough up high cards in other suits while running it out of trumps. The player decides to wait to play the 10♣, which at that point is their last trump, opting instead to play the Q♥, since the A♥ has already fallen. The deck responds 10♦ before coughing up 4♣, winning the trick.

The deck leads the K♠ next, which player must respond with 4♠; next comes the 4♦ which player must answer with 3♦. The Q♦ is led out of the pack next. Since player is out of diamonds at that point, they decide to use the joker in their hand, losing the trick but keeping other options open. The deck’s next lead is 2♥; here the player answers with 7♥, winning a trick they didn’t expect.

Player next leads the 9♠, only for the deck to answer with a joker, costing the player that trick. The next card out of the deck is 6♦, which the player collects with their last trump. On the final trick, the player leads the 8♥, the last card in their hand, which the stock collects with the 5♣. In all, the player won seven tricks during the course of game play, sufficient to make the contract, earning them 40 points below the line, 150 above the line for five honors, and 50 above the line for insult.

Example 2

After dealing the cards, a player winds up with this face-up set of cards: A-10-3-2♥, 7-6-2♦, K-4-2♣, 10-5-4♠. There’s not much to work with here—the diamonds and spades don’t offer up tricks, while the K♣ is only good if the player takes one of the other clubs. Ultimately that’s what that player chooses to do, taking all four hearts in the hope of getting something with some length to it. The player picks up the face down cards, and winds up with this hand: A-Q-10-3-2♥, 3♦, K-4-3♣, A-9-3♠, ★, receiving precious little help there.

The K♣ is a winning trick, as is the A♠. In the hearts suit, the player has the A♥, would lose the 2♥ to the K♥, making the Q♥ good, and would lose the 3♥ to the J♥, making the 10♥ good, so three winning tricks there. The player has five tricks in their hand and their short suit is diamonds, so the deck bid for the hand is 1♦. The player isn’t entirely confident in their hand, but still elects to go ahead and bid 1♥. The final contract is at 1♥ Doubled.

The deck opens play with J♥, which the player counters with the Q♥. Going for broke, the player plays the A♥. The deck answers first with Q♦, an invalid play, but the next turn up is the other joker, which goes to the deck. Needless to say, this particular hand winds up going very badly for the player, who might’ve been better off had they decided to defend rather than bid…![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Back Alley

Back Alley, also sometimes known as Back Alley Bridge, Back Street Bridge, or Blooper, is a trick-taking game for four players in partnerships.

Back Alley originated as a non-partnership game played by members of the U.S. military during World War II. The version of the game described here developed later, most likely during the Vietnam War.

Object of Back Alley

The object of Back Alley is to take as many tricks as possible, as well as accurately bidding how many tricks you expect to take.

Setup

Back Alley is played with a 54-card deck, formed by augmenting a standard 52-card deck with two jokers. The two jokers must be different from one another, as one must serve as the big blooper and the other as the little blooper. Denexa 100% Plastic Playing Cards fit the bill perfectly, since one of the jokers has a dragon (the big blooper) and the other a jester (the little blooper). It should be clearly stated to the players before the game begins which joker will represent which blooper.

You also need something to keep score with. Pencil and paper is what most people use for this, but you can use whatever’s convenient, such as a smartphone application developed for the purpose.

Determine partnerships through whatever means are convenient, such as high-card draw or mutual agreement. Each player should be seated opposite their partner, such that the turn of play alternates partnerships as it goes clockwise around the table.

Shuffle and deal thirteen cards to each player. (This number will vary on subsequent hands, see below.) Turn the next card face up; this card, the upcard, fixes the trump suit. If the upcard is a joker, the hand is played with no trump, and the player who holds the other joker must discard it and take the last card of the deck to replace it. Otherwise, the last card in the deck remains face down and takes no part in game play.

Game play

Cards rank in their usual order, with aces high. The big blooper is the highest trump, with the lower blooper ranking just below it. Both bloopers outrank the ace of trumps.

Bidding

Each player in turn, going clockwise around the table, gets one chance to bid. The player to the dealer’s left bids first, and bidding ends after the dealer’s bid. Players may make a bid that they will take any amount of tricks from one to twelve. They may also pass, which is essentially a bid of zero. If all four players pass, then the cards are shuffled and the same dealer deals new hands. Otherwise, each side adds their two bids together, and this number becomes the contract for the following hand.

In addition to these bids, one player may also make a bid of board. This is a bid to take all of the tricks. If a player wishes to bid board whenever someone has already bid it, they may bid double board. Subsequent players may likewise bid triple board or quadruple board, as appropriate. Such bids multiply the risk and reward of bidding board.

Play of the hand

The player who bid highest leads to the first trick. If multiple players are tied for high bid, the first one in the bidding order goes first. If multiple players bid board, the player who made the highest board bid goes first.

Each player, proceeding clockwise from the leader, plays one card to the trick. Players must follow suit if they can. Otherwise, they may play any card, including a trump. Whoever played the highest trump, or the highest card of the suit led, wins the trick. They collect the cards and place them face-down in a won-trick pile that they share with their partner. (Since the number of tricks collected matters, it’s a good idea to place each trick at right angles to the previous one in order to make it easier to count them later.)

There are some special rules about leading trumps. Trumps cannot be led until trumps have been broken, that is, a trump has been played to a trick without being led to it. If the big blooper is led, every player must play the highest trump they hold in their hand. When the little blooper is led, each player is required to play the lowest trump that they hold. (The only way the little blooper can be defeated when led is if another player holds the big blooper as their only trump.)

Scoring

After the players have exhausted their hands, the hand is scored. Each partnership counts the number of tricks that they won. If a team captured at least as many tricks as they bid, they have made their contract. They score five points for each trick bid, plus one trick for each additional trick collected. If a team fails to make their contract, they lose five points for each trick bid.

If a team bids board, they win or lose ten points per trick, depending on whether or not they collected all of the tricks or not. Teams bidding double, triple, or quadruple board score ±20, 30, or 40 points, respectively.

The second through 26th hands

The deal passes to the left. On the second hand, only twelve cards are dealt. The third hand is played with eleven cards, and so on, until the thirteenth hand, which consists of only one card. The fourteenth hand is also a one-card hand, after which the number of cards begin increasing again. The hand size again reaches thirteen cards on the 26th hand. The game ends after the 26th hand has been played. Whichever partnership has the higher score at that point wins the game.![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Carousel

Carousel is a rummy-type game for two to five players. Carousel is one of a small family of “manipulation rummy” games. The chief feature of this group that all of the melds on the table are shared between the players. Players can lay off on any meld on the table, and not only that, they can move cards between melds, break them apart, and reform them at will! Rummikub, a proprietary tile-based game, fits into this game family quite well, and was probably derived from one of its members.

Object of Carousel

The object of Carousel is to get rid of as many cards as possible by putting them into melds. That allows a player to knock, hopefully ensuring that the total of their unmatched cards is lower than that of their opponent.

Setup

The number of cards used in Carousel depends on the number of players. For two players, use one deck of Denexa 100% Plastic Playing Cards, including one joker. For three to five players, use two decks with two jokers. You’ll also need something to keep score with, such as the traditional pencil and paper, or a smartphone app dedicated to the task.

Shuffle and deal ten cards to each player. Place the rest of the deck face down in the center of the table, forming the stock.

Game play

The player to the dealer’s left goes first. A player begins their turn by drawing one card from the stock. If they are able to meld, they may do so, melding as many cards as they legally can. Once they are done melding, their turn ends, and play passes to the next player to their left. If they cannot or do not wish to meld, they may draw a second card from the stock. Again, they may meld after their second draw if they can, which ends their turn. Otherwise, they draw a third card from the stock and their turn ends at that point. (Unlike most other rummy games, there is no discarding.)

Each card has a point value assigned to it. Jokers are worth 25 points each, face cards are worth 10 points each, and aces are worth 1 point each. All other cards are worth their pip value.

Melding

There are two types of valid melds in Carousel. The first is a set, which consists of three or four cards of the same rank and different suits. You cannot have two cards of the same suit in a set.

The second type of meld is a sequence, which is made of three or more consecutive cards of the same suit. For the purpose of sequences, cards rank in their usual order. Aces may start or end a sequence, but cannot be in the middle (A-2-3 and J-Q-K-A are both perfectly fine sequences, but K-A-2 is not).

When melding, you may rearrange the cards on the table to whatever combination of meld you see fit. For example, you may take a 10 from a set of four 10s on the board to use it in a run. Or you can take a card off the end of a run of more than three cards to form a set. The important thing is that at the end of your turn, every card on the table must still be part of a valid meld. (You cannot, say, take a card from the middle of a sequence, or leave only two cards in a meld.) You cannot take any cards from the table and put them into your hand.

Below is an example of a meld a player might make. Suppose two of the melds previously on the table were 8-9-10-J♦ and J-Q-K-A♠. The active player has the J♥ in their hand. They may remove the J♦ and J♠ from their existing melds and combine them with the J♥ from their hand in order to form a new meld of three jacks. The melds on the table at the end of the hand would be 8-9-10♦, Q-K-A♠, and J♦-J♠-J♥.

Using the joker

The joker is wild and can represent any other card in the meld. When playing a joker, you must specify the exact rank and suit of the card that it represents. The joker is then treated as though it is a natural card of that rank and suit. The joker can only be moved to a new meld where the card it represents would legally fit.

If the natural card that a joker is substituting for is in play, a player may remove the joker from its meld and add the natural card in its place. The natural card can come from either the player’s hand or another meld. The joker can then be moved to a different meld. It can once again represent any card that the player names. The joker cannot be returned to the player’s hand, however.

Going out

If a player ends their turn with less than five points in deadwood (unmatched cards), they may knock before the next player takes their turn. This ends the hand immediately, and no further melding may take place at that point. All players reveal their hands and total their deadwood score. The player who knocked wins the hand, unless any of their opponents has a lower or equal deadwood total. In that case, the player with the lowest score wins and scores a ten-point bonus for undercutting. (In the event that multiple players tie for the lowest deadwood score, every tied player other than the player who knocked is considered to have won and scores accordingly.) If a player melds all of their cards (and thus has a deadwood score of zero), they score a 25-point bonus.

The winner’s hand score is determined by calculating the difference between the winner’s deadwood and that of each of their opponents. They then total all of the differences, along with any relevant bonuses, as described above. No other players score for that hand.

The deal passes to the left and new hands are dealt. Game play continues until one player reaches a score of 150 or more. That player is the winner, and receives a game bonus of 100 points. Each player also scores a 25-point box bonus for each hand that they won.![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Kaiser

Kaiser, also known as Joffre, Three-Spot, or Troika, is a trick-taking game played throughout Canada, especially in the Ukrainian and First Nations communities of Saskatchewan. It is played with four players in partnerships.

Object of Kaiser

The object of Kaiser is to take the most tricks. Special attention is given to taking the trick containing the 5♥, and avoiding the trick containing the 3♠.

Setup

Kaiser is played with a unique setup of cards. Starting from a deck of Denexa 100% Plastic Playing Cards, remove all of the 6s through 2s. Then, remove the 7♥ and 7♠. Finally, return the 5♥ and 3♠ to the deck, bringing it to a total of 32 cards. You’ll also need something to keep score with, like the tried and tested pencil and paper.

Choose partners by whatever method is convenient, be it a random method like high-card draw, or just mutual agreement. Partners must sit across from each other, such that the turn of play alternates between partnerships as it goes around the table.

Shuffle and deal out the entire deck. Each player will get eight cards. If a player receives a hand with no aces, face cards, 5♥, or 3♠, they may declare a misdeal. All four players throw in their cards, and the same dealer deals new hands.

Game play

Bidding

After the players have had a chance to take a look at their hands, players bid to fix the trump suit. The player to the dealer’s left has the first opportunity to bid, and each player proceeding clockwise must either bid higher. Any player may also pass. The final bid goes to the dealer, who has the privilege of being able to simply equal the previous bid rather than overcalling it. There is only one round of bidding; each player only has one chance to bid.

The minimum bid is six points. Players may also make no trump bids (stated with “no” after the number, e.g. “seven no”), which outrank a normal bid of the same amount. No trump bids increase the risk and reward of the contract. The highest possible bid is twelve no.

After the bidding has concluded, the player with the winning bid names the trump suit. They and their partner become the declarers. The other partnership becomes the defenders. The declarers’ high bid becomes their contract, their goal score for the hand.

Play of the hand

The player to the dealer’s left leads to the first trick. Each player in turn then plays to the trick. Players must follow suit if able; otherwise, they may play any card, including a trump.

After all four players have played to the trick, the person who played the highest trump, or the highest card of the suit led if no trumps were played, wins it. Cards rank in their usual order, with aces high.

The player winning the trick takes the cards and places them in a face-down won-tricks pile in front of one of the partners. (Since the number of tricks won matters, it’s a good idea to place each trick at right angles to the previous one to keep the tricks identifiable.) The winner of the trick then leads to the next one.

The hand continues until eight tricks have been played and the players have exhausted their hands.

Scoring

After the hand has been completed, the partnerships each tally up the value of their won tricks:

- One point for each trick

- Five points for capturing the 5♥

- ‒3 points for capturing the 3♠

If the declarers made their contract, they add the value of their tricks to their score. However, if they broke the contract, they subtract the value of the tricks. If the contract was played at no trump, then the trick score is doubled before being added to or subtracted from the score.

If the defenders have a score of 45 or less, they add the values of their collected tricks to their score, regardless of whether or not the declarers made their contract. Note that it’s possible for the defenders to have a negative hand score, if they captured the 3♠ but less than three tricks. (In this case, their game score actually goes down.) If the defenders have a score greater than 45, their score is only affected if they have a negative hand score.

New hands are dealt and game play continues until one team reaches a score of 52 or more. The partnership with the higher score wins the game.![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()