Indian Chief

Indian Chief is a unique rummy game for two to eight players. It bears a slight similarity to the Contract Rummy subfamily of games, due to its requirement to form a particular series of melds. Unlike the Contract Rummy games, however, the order that the melds are formed doesn’t matter, so long as the cards melded can be counted as something. In this way, the game is more akin to the dice game Yacht than many card games!

Indian Chief was created by Stven Carlberg of Decatur, Georgia. He posted its rules to the BoardGameGeek forum in January 2009. The game was very well received there; several players created additional scoresheets and reference materials for it. It continues to be actively recommended by the site’s userbase to this day.

Object of Indian Chief

The object of Indian Chief is to form the highest-scoring instances of the game’s seven melds.

Setup

Indian Chief uses one standard 52-card deck of playing cards, when playing with two or three players, and two standard decks if you’re playing with more than that. If you’ve got some Denexa 100% Plastic Playing Cards handy, why not use those?

Indian Chief uses one standard 52-card deck of playing cards, when playing with two or three players, and two standard decks if you’re playing with more than that. If you’ve got some Denexa 100% Plastic Playing Cards handy, why not use those?

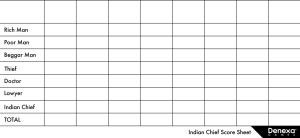

You also need a Indian Chief score sheet and something to write with. If you want, you can print off ours (shown to the right; click on it to bring it up full-size). Otherwise, just copy it down onto whatever sort of paper is handy. Most people will use something like a piece of notebook paper, but if you want to scribble it down on the back of a junk mail envelope, well, you do you.

Shuffle and deal eight cards, face down, to each player. Set the deck stub aside.

Game play

Players look at their hands and decide on which meld they wish to form. They take the cards forming that meld from their hand and, at a signal, all players reveal their melds simultaneously. The value of each player’s meld is calculated and recorded in the appropriate box on the score sheet under their name.

Players do not have the option to simply not meld—a player must make a meld on every turn. Because each meld includes a different number of cards, it is obvious which meld a player is attempting to make by the number of cards they reveal. If the revealed cards don’t qualify for the meld attempted, the player simply enters a score of zero in that box. Players may not attempt to re-make a meld that they already have a score written down for (e.g. if you already have a number in the “Doctor” box, you cannot make another six-card Doctor meld).

Once the melds have been scored, the dealer replenishes everyone’s hands back up to eight cards from the deck stub. The melds from the previous round are then collected and restored to the deck. The deck is then shuffled in preparation for the next turn.

The melds

Below are the seven possible melds (each named after a line in a Mother Goose rhyme) in Indian Chief. When a card’s “face value” is referred to, aces are worth one point, face cards are worth ten points, and all other cards their pip value. The number next to each meld is the number of cards it contains.

- Rich Man (5): Any five cards. The face values of these five cards are added together and placed on the score sheet as a negative value.

- Poor Man (3): Any three cards. The face values of any spades melded are added together to determine the score for the meld.

- Beggar Man (2): Any two cards. Score two points for each of the cards in the opponent’s melds that match the Beggar Man cards in rank.

- Thief (1): Any one card. Score its face value. After the melds have been scored, a player melding the Thief may steal a card from an opponent’s meld instead of being dealt an unknown card from the deck. If multiple Thieves have been played on one turn, they steal in order from the lowest card played to the highest. If there’s a tie, they must agree to steal different cards, or neither of them may steal.

- Doctor (6): Six cards of all different ranks, one of which must be a heart, and one of which must be an ace. If all conditions are met, the player names a suit and scores ten point for each of the cards in the meld of that suit. Otherwise, score zero.

- Lawyer (4): Four cards whose face values add up to exactly 25. If they do, score 25 points; otherwise, score zero.

- Indian Chief (7): A five-card poker hand (see rank of poker hands) and a two-card Baccarat hand. Score the Baccarat hand first, by adding the values of the two cards, then dropping the tens digit. Add the value of the poker hand, as listed below, to get the total score for the meld:

- Five of a kind: 50 points.

- Straight flush (including royal flushes): 45 points.

- Four of a kind: 40 points.

- Full house: 35 points.

- Flush: 30 points.

- Straight: 25 points.

- Three of a kind: 20 points.

- Two pair: 15 points.

- Pair: 10 points.

- High card: 5 points.

Ending the game

The game ends after seven turns, after which each player will have filled up their score sheet. The players’ scores for each meld are simply totaled, and the player with the highest score wins.

External link

- Original post at BoardGameGeek (includes an explanation of how the melds relate to their names)

Bridge Solitaire

Bridge Solitaire is a one-player variant of Contract Bridge invented by Stephen Rogers. In Bridge Solitaire, a player follows the typical flow of a Bridge hand, from bidding through play of the hand. The undealt cards in the deck serve as the player’s “opponent”.

Rogers shared the game with us at our Card Game Night event here in Norman in December 2016. It borrows some play mechanics from Natty Bumppo’s Euchre Solitaire game, published on John McLeod’s Pagat.com. Rogers created the game as a response to the difficulties finding three other willing participants for a true Bridge game. He bestowed the game with an alternate title, You People Suck, in reference to those who would rather spend time on their phones than play a game of Bridge!

Object of Bridge Solitaire

The object of Bridge Solitaire is score as many points as possible playing a game of Contract Bridge against the deck stub. Points are scored by accurately predicting the number of tricks in excess of six that you will be able to win. The ultimate goal is to thus win two games, which constitute a rubber.

Setup

Bridge Solitaire uses the same standard 52-card pack that Contract Bridge uses, plus two jokers. We’re not certain if Bridge Solitaire was invented with a pack of Denexa 100% Plastic Playing Cards. We’re pretty sure they’re the cards the game is most frequently played with, though!

You also need a typical Bridge scoring sheet. Pre-printed ones exist; they’re ruled into four quadrants, the columns headed by ‘WE’ and ‘THEY’. If a pre-printed scoresheet isn’t handy, you can easily make one by simply dividing a sheet of paper with a vertical and a horizontal line. (‘WE’ and ‘THEY’ seem a little pretentious if you’re playing solitaire, though. ‘ME’ and ‘IT’ are probably more appropriate, or ‘PLAYER’ and ‘HOUSE’ if you feel like being more serious about it.)

Shuffle and deal seven cards face down without looking at them. Then, deal thirteen cards face up in front of you. The deck stub becomes the stock, which will serve as the player’s opponent for the rest of the hand. For the sake of clarity, we’ll refer to the theoretical player the deck is representing as the house.

Game play

Cards rank in their usual order, with aces high. The jokers (★) do not have any rank and cannot win or lose a trick.

Determining the player’s hand

The player begins by choosing their hand. The seven face-down cards will be part of their hand no matter what, and they cannot change any of these cards. Before looking at them, though, they do get to choose the other six cards in their hand from the thirteen face-up cards available to them. If there are any jokers in these thirteen cards, the player is obliged to take them. Otherwise, the player is free to select cards however they see fit.

The unchosen cards are discarded in a face-up discard pile, and the face-down cards are turned up. The chosen cards are added to these previously-unknown cards, allowing the player to see their full thirteen-card hand. The discarded cards (save for the top card of the discard pile) cannot be inspected after this point; if a player wishes to use information from them, they must commit it to memory.

Bidding

After the hand has been determined, the play proceeds to bidding. Bids function the same as they do in Contract Bridge. Each bid consists of a number of odd tricks (tricks in excess of six) that the player is committing to take. This is combined with a suit that the player is proposing to make trump, or “no trump”. From lowest to highest, the suits rank clubs, diamonds, hearts, spades, no trump. Therefore, the lowest bid is 1♣, which would be overcalled by a bid of 1♦, and so on up to 1♠, then 1NT, which would be overcalled by 2♣.

The house always bids first; its bid is determined by the contents of your hand. The house will bid the suit that the player has the least cards in. The numerical content of the bid is calculated by examining each suit and counting the number of “winning tricks” the player can make. For example, in diamonds, the player has A-Q-10-9. The A♦ would win a trick (being the highest diamond), the 9♦ would lose to the K♦ (which is held by the house), the Q♦ then wins a trick (being the highest unaccounted-for diamond), and the J♦ would take 10♦, so the player has two winning tricks in diamonds. The sum of the values from each of the four suits is subtracted from six. If the result is zero or negative, the house passes. Otherwise, the resulting value (combined with the player’s short suit) is the house’s bid.

No Trump bids may only be made when the player holds one of the following suit distributions: 4-3-3-3, 3-3-3-3-★, 3-3-3-2-★-★.

If the house passes, the player is required to make a bid. Otherwise, the player has the option to overcall the house and play as declarer. They may also pass, and play as defender.

If the player holds one joker, the contract is doubled. If holding two jokers, it is redoubled.

Play of the hand

The play of the hand is conducted according to the usual Bridge rules. Both the player and the house must follow suit if possible. If the player is unable to follow suit, they may play any card. The highest played card of the suit led wins the trick, unless a trump was played. In that case, the highest trump wins.

Whichever player is defending leads to the first trick. When the house leads, it does so by simply playing the top card of the stock. If the player leads, cards are turned over from the stock until a card that can be legally played is exposed. The trick is then placed in one of two discard piles (one for the player and one for the house), face down. Since it is important to keep track of the number of tricks captured, it may be helpful to place each trick onto the pile at right angles. This allows the tricks to be easily separated after the hand. The player that won the trick leads to the next one.

A special rule applies during No Trump contracts. When the player leads, the house may play a maximum of only four cards from the stock. If, by the fourth card, the house has not made a legal play, the player wins the trick by default. They then lead to the next one, as usual.

Jokers have a special role in the game. If the player cannot follow suit, they may respond with a joker instead of playing any other card. If the house leads a joker, the player may play any card they wish. The house wins any trick containing a joker, with one exception. Should the player respond to a joker led by the house with the other joker, the player wins the trick instead. (A player may presumably lead a trick with a joker as well. There seems to be little point in doing so, however.)

The hand ends when thirteen tricks have been played, meaning that the player has run through their entire hand. In the event that the stock is exhausted before the hand is completed, the last card of the stock is the house’s play for the last trick. Each remaining card in the player’s hand is considered a trick won by the player.

Scoring

Scoring is done according to typical Contract Bridge scoring rules.

Example hands

The following hands, and the accompanying commentary, were given to us by Rogers to help illustrate the game:

Example 1

After shuffling, a player deals out seven face-down cards face down into a pile, and then thirteen cards face-up, setting the rest of the deck aside to form the stock. The thirteen face-up cards look like this: J-10-7-2♠, 9♦, A-K-10-8♣, Q-8-5-4♥.

The player, not particularly thrilled with this draw, begins weighing their options of which cards to keep. The 9♦ is an obvious throwaway, while A-K♣ will automatically give them two winning tricks against the stock. Taking Q-8-5♥ would also guarantee a third trick in hearts, but taking half the potential draw for a single trick seems unwise, and going J-10-7-2♠ for a single trick in spades is right out. The player ultimately selects A-K-10-8♣, Q-8♥, throwing out the other face-up cards into a face-up discard pile with the J♠ on top, a reminder that they threw away one of the honors in that major suit. This gives them two tricks for sure and a potential third if the face down cards include at least one lower-ranked heart.

The player then picks up the seven face-down cards and, having looked them over, happily adds them to their hand—the final disposition of their hand is: A-K-Q-J-10-8♣, Q-8-7♥, 9-4♠, 3♦, ★.

Next, they need to evaluate their hand for the deck bid—here it’s an easy thing to determine. With five honors in clubs, they have five winning tricks in that suit. They were also given another heart, so the queen is good for a trick there. Diamonds and spades are duds, but it doesn’t matter—the player has six tricks in hand, so the deck will pass. The player decides to play conservatively since they have two suits without stoppers in them, and bids 1♣. Thanks to the joker in their hand, the final bid is 1♣ Doubled.

Since the player bid to play, a card is dealt off the top of the stock, in this case the 3♣, which the player counters with 8♣, winning the first trick. The player then leads the A♣ and draws the next card off the stock, which is the 7♦. Since this is neither a trump nor a card of the suit led, it is ignored and another card is dealt, the 5♦. This is also invalid—the A♥ is turned up (something of which the player takes note) before the deck finally yields up 9♣, a valid play. Player wins the second trick.

The player plays their next three trump honors in sequence, forcing the deck to cough up high cards in other suits while running it out of trumps. The player decides to wait to play the 10♣, which at that point is their last trump, opting instead to play the Q♥, since the A♥ has already fallen. The deck responds 10♦ before coughing up 4♣, winning the trick.

The deck leads the K♠ next, which player must respond with 4♠; next comes the 4♦ which player must answer with 3♦. The Q♦ is led out of the pack next. Since player is out of diamonds at that point, they decide to use the joker in their hand, losing the trick but keeping other options open. The deck’s next lead is 2♥; here the player answers with 7♥, winning a trick they didn’t expect.

Player next leads the 9♠, only for the deck to answer with a joker, costing the player that trick. The next card out of the deck is 6♦, which the player collects with their last trump. On the final trick, the player leads the 8♥, the last card in their hand, which the stock collects with the 5♣. In all, the player won seven tricks during the course of game play, sufficient to make the contract, earning them 40 points below the line, 150 above the line for five honors, and 50 above the line for insult.

Example 2

After dealing the cards, a player winds up with this face-up set of cards: A-10-3-2♥, 7-6-2♦, K-4-2♣, 10-5-4♠. There’s not much to work with here—the diamonds and spades don’t offer up tricks, while the K♣ is only good if the player takes one of the other clubs. Ultimately that’s what that player chooses to do, taking all four hearts in the hope of getting something with some length to it. The player picks up the face down cards, and winds up with this hand: A-Q-10-3-2♥, 3♦, K-4-3♣, A-9-3♠, ★, receiving precious little help there.

The K♣ is a winning trick, as is the A♠. In the hearts suit, the player has the A♥, would lose the 2♥ to the K♥, making the Q♥ good, and would lose the 3♥ to the J♥, making the 10♥ good, so three winning tricks there. The player has five tricks in their hand and their short suit is diamonds, so the deck bid for the hand is 1♦. The player isn’t entirely confident in their hand, but still elects to go ahead and bid 1♥. The final contract is at 1♥ Doubled.

The deck opens play with J♥, which the player counters with the Q♥. Going for broke, the player plays the A♥. The deck answers first with Q♦, an invalid play, but the next turn up is the other joker, which goes to the deck. Needless to say, this particular hand winds up going very badly for the player, who might’ve been better off had they decided to defend rather than bid…

Jersey Gin

Jersey Gin is an adaptation of Gin Rummy for three players. A three-player Gin game similar to this one first surfaced in Jersey City, New Jersey, where it was discovered by noted card game expert John Scarne. Scarne analyzed the rules of the game and found them to be “full of mathematical bugs”; he took the liberty of correcting the rules to make them fairer. He then published his corrected rules under the name “Jersey Gin”.

Object of Jersey Gin

The object of Jersey Gin is to arrange your hand into melds and be the first to knock, hopefully ensuring that the total of your unmatched cards is lower than that of your opponent.

Setup

To play Jersey Gin, you’ll need one standard 52-card deck of playing cards. We’d be pretty pleased to know that you’re using a deck of Denexa 100% Plastic Playing Cards. You should also have something to keep score with, like a pencil and paper.

Shuffle and deal ten cards, face down, to each player. Place the stub in the center of the table, forming the stock. Turn the top card of the stock face up; this card, the upcard, is the first card of the discard pile.

Game play

Everything in Jersey Gin revolves around melds. Three or four of a kind is one type of meld. Another is a run or sequence of three or more cards of the same suit, in sequence, such as 5-6-7♣. Cards rank in their usual order. Aces are always considered low, and cannot be used consecutively with the king. That is, neither Q-K-A nor K-A-2 are considered valid melds.

Each card also has a point value in Jersey Gin. Aces have a value of one point, face cards have a value of ten. All other cards are worth their face value. These values are used to calculate a player’s deadwood, the value of the cards in their hand that cannot be formed into melds.

Play of the hand

The player to the left of the dealer goes first. They start their turn by drawing one card. This may be either the top card of the discard pile or the top card of the stock. They then end their turn by discarding a card, face up, from their hand. Play then passes to the next player to the left, who does the same thing, and so on and so forth.

The discard pile should be kept squared up at all times: fishing through the discards is prohibited. If a player wants to use the information of what the discard pile contains, it is their responsibility to remember what has been discarded throughout the game.

Ending the hand

When a player’s deadwood score reaches ten or less, they may knock by discarding their card face-down and knocking on the table. Each player then lays their hand face up on the table, with each meld identifiably broken out. The two players that didn’t knock may reduce their deadwood counts by adding cards to their opponents’ melds, which is known as laying off. The difference between the knocker’s score and that of each of their opponents is added together to arrive at the knocker’s total score for the hand. For instance, a player knocks with a deadwood count of 9, while their opponents have 11 and 14. The knocker scores (11–9) + (14–9) = 7 points for the hand.

If the player with the lowest underwood score is not the player who knocked, the lowest player is said to have underknocked. They score for the hand as if they had knocked, plus a ten-point underknock bonus.

Rather than knocking, a player may elect to continue playing until their deadwood score reaches zero. When this happens, they declare gin and reveal their hand, scoring the opponent’s deadwood total plus a 40-point bonus. The opponents may not lay off deadwood on a gin hand.

After the end of the hand, the deal rotates for the next hand. Game play continues until a player reaches 100 points. This player then scores an additional 100 bonus points. Each player scores a box bonus of 25 points for each hand that they won.

The break (when the stock runs out)

Unlike in standard Gin Rummy, the game doesn’t just end when the stock runs out. Instead, when the stock is reduced to three cards, the break occurs. The next player to draw is called the breaker. Special rules apply after the break. Players cannot knock, and a card can only be drawn from the discard pile if it can immediately be used in a meld.

After the breaker completes their turn, they lay their melds face up, keeping their deadwood concealed in their hand. The next person to play draws, then lays their melds out in the same way, and may lay off any cards that they can on the breaker’s melds. The third player completes their turn similarly, with the opportunity to lay off on either of their opponents’ melds. If there are still cards left in the stock, then it is the breaker’s turn again, who may now lay off on any meld.

If a player goes gin, it is handled in the usual way, as described above. Otherwise, the hand continues until the stock is completely out of cards and the final player has discarded. At that point, the hand is scored, treating the player with the lowest deadwood as though they had knocked. If there is a tie involving the breaker, the breaker wins it; if the other two players tie, the player to the left of the breaker wins it.

See also

Pitch

Pitch (also known as Setback) is a trick-taking game played in the United States. In the Midwest and central parts of the United States, it is most commonly played as a partnership game. On the coasts, Pitch is more frequently played as a cutthroat, every-player-for-themselves game, often for money. The four-player partnership game is described here.

Pitch is essentially an American adaptation of the old English pub game All Fours. Pitch uses a more conventional bidding system to fix the trump suit, rather than the more complicated procedure found in All Fours.

Object of Pitch

The object of Pitch is to be the first team to score 21 or more points by successfully fulfilling bids.

Setup

Pitch is played with a standard 52-card deck of playing cards. Because you need a deck of cards that can stand up to whatever you throw at it, make sure you always use Denexa 100% Plastic Playing Cards.

Partnerships may be determined by any agreed-upon method, including mutual agreement or any sort of random process. Partners should sit across from each other, so as play proceeds clockwise, each player’s turn is followed by one of their opponents’ turns.

Shuffle and deal six cards to each player, in two batches of three. The stub is set aside and is not used for the rest of the hand.

Game play

Game play in Pitch revolves around scoring points for the following achievements:

- High—playing the highest trump in play during the hand,

- Low—capturing the lowest trump in play during the hand,

- Jack—capturing the jack of trumps,

- Game—accruing the highest total of cards captured during the hand, scoring as follows: ten for each 10, four for each ace, three for each king, two for each queen, and one for each jack. 9s and below do not count toward the game score. If the teams tie for game, the point is not scored.

Because not all of the cards are dealt on each hand, the trump scoring for High is not necessarily the ace, and the trump scoring for Low is not necessarily the two. Likewise, the point for Jack sometimes goes unscored, since the jack of trumps is not always in play.

Bidding

The right to choose the trump suit is given to the player who makes the highest bid. Available bids in Pitch are two, three, four, and smudge. The first three of these bids represents a commitment to score at least that many points on the following hand. A bid of smudge, the highest bid, is a bid to score four points plus all the tricks. However, by bidding four or smudge, you may unknowingly get yourself into a situation where it is impossible to make your bid. The jack of trumps is not always dealt, and in hands where this is the case, the point for Jack is not scored, meaning the most you can score is three. Even if you take all six tricks, you will not make your contract.

Bidding begins with the player to the dealer’s left. They may either bid or pass. Bidding continues clockwise, with each player passing or making a higher bid than the players before them. The dealer makes the last bid, and has the right to bid the same as the player before them, called stealing the bid. If every player passes, the dealer is compelled to make a bid of two, called a force bid. There is only one round of bidding; the high bid stands after the dealer makes their bid. The player making the high bid is called the pitcher.

Play of the hand

The pitcher leads to the first trick. The suit of the card they lead off with becomes the trump suit. Each other player plays to the trick in turn, proceeding clockwise. Each player must follow suit, unless they are unable, in which case they may play any card. Additionally, playing a trump is always allowed, even if the player could follow suit. The player who plays the highest card of the suit led (aces rank high) collects the trick, unless a trump is played, in which case the highest trump played wins the trick. Collected tricks are not added to the player’s hand, but rather a score pile shared with their partner. The winner of each trick leads to the next one.

Ending the hand

When all six tricks have been played, the hands are scored. If the pitcher’s team makes at least as many points (as described above) as they bid, they score one point for each point made. When a bid of smudge is made, the pitcher’s team scores five points (the four points they scored, plus one for the smudge). If the pitcher’s team failed to make their bid, they are said to have been set. They are set back the amount of their bid instead, i.e., the value of their bid is deducted from their score. Regardless of if the pitcher’s team makes their bid or not, their opponents always score the number of points they made.

The deal passes to the left, the cards are shuffled, and new hands are dealt. Game play continues until a partnership reaches a score of 21 or more after having successfully made their bid. Note that it’s possible for a team to score above 21 while not being the high bidders. In this case, the team must remain above 21 points and successfully make a bid before they can win. (In some cases, the winning team may even have a lower score than their opponents, simply because they made a winning bid and crossed 21 before their opponents, already over 21, could.)

See also

Pitch is one of those games with lots of variations—tell us how you like to play in the comments!

Democracy

Democracy is a trick-taking game for two to six players. Although its precise origins are not known for sure, it is popular at the Tabletop Board Game Cafe in Cleveland, Ohio, and has been played there since at least 2004. It seems plausible that the game originates from Cleveland, perhaps being invented by one of the cafe’s patrons.

Unlike most card games, Democracy has a backstory: the players play the part of colonial powers attempting to annex an island inhabited by four tribes, which are represented by the four suits. The countries decide to resolve the question of which one of them will gain control of the island by putting it up to a vote of the people of the island. The night before the vote, though, the countries kidnap a few members of the tribes under cover of darkness, not knowing for sure which members of which tribes they’ve captured. The day of the vote, the captured tribal members make impassioned speeches in favor of the countries that have captured them—presumably under threat of death, of course. Thus, the name Democracy is certainly intended to be firmly tongue-in-cheek. Of course, the “speeches” are the tricks played by the players, and the winner of the trick is the card that have the “most persuasive speech”.

Democracy is often played with very loose adherance to the rules. When played this way, the game play is more akin to a roleplaying game like Dungeons & Dragons than to a traditional card game. In some games, the rules are entirely negotiable; the cards carry only a suggestion of value, with the players’ tribespeople arguing in support of the nation holding them in the form of verbal speeches given by the players! While a higher-ranking card has innate advantages over the lower-ranked cards, a well-received speech by a charismatic player might well take the trick regardless of whether it was the highest-ranked card played. We recommend sticking to the rules to start out with, but if you wish to add these roleplaying elements to the game later, have at it!

Object of Democracy

The object of Democracy is to capture, through trick-taking, a majority of points in as many suits as possible.

Setup

Democracy is played with a modified 52-card deck with a number of cards added or removed depending on the number of players. Starting with a deck of Denexa 100% Plastic Playing Cards:

- For two, three or five players, remove the 2s, leaving a 48-card deck (3 through ace in all four suits).

- For four players, remove the 2s and add two jokers, creating a 50-card deck.

- For six players, remove the 2s and add one joker, creating a 49-card deck.

Shuffle and deal amongst the players and an extra hand, called the voting pool:

- For two players, twelve cards.

- For three players, eight cards.

- For four players, six cards.

- For five or six players, four cards.

This deal is called the first day.

Rank of cards

In Democracy, the cards rank in an unusual order. The 5, 4, and 3 are moved from their normal spots to become the highest three cards in the game. So the full rank of cards is: (high) 5-4-3-A-K-Q-J-10-9-8-7-6 (low).

In the game’s story, each rank is linked with a social class within each of the tribes. Each card also has a point value:

- 5: the chief (five points)

- 4: the chieftainess (four points)

- 3, A: the warriors (three points)

- K, Q, J: the hunters (two points)

- 10, 9, 8, 7: the farmers (one point)

- 6: the village idiot (zero points)

Game play

Each trick begins with the dealer turning the top card of the voting pool face up; this card, the upcard, determines the trump suit for the trick. Each player then chooses a card to play to the trick and places it face down in front of them. Unlike in most trick-taking games, there is no requirement to follow suit or trump if possible—the player may select any card they desire. Once everyone has played a card, on the count of three from the dealer, all players simultaneously turn their cards face up.

The trick is won by the highest trump played to the trick, unless both the 5 and 6 of trump are present, in which case the 6 wins over the normally unbeatable 5 of trump. If no trump is played to the trick, the highest card played wins the trick. (Note that the actual ranks of the cards determines who wins the trick, not the cards’ point values; kings and queens are both two-point hunter cards, but a king still beats a queen.) A player winning the entire trick places the cards comprising it, including the upcard, into a face-down won-tricks pile. In the event that two cards of different suits tie for highest, each player simply wins their own card and the upcard is discarded.

Jokers are wild for any card other than a trump. In practice, this usually means that they represent a non-trump 5, and will win the trick unless a trump or another 5 is played to the trick. Captured jokers do not score anything; playing them is simply an attempt to capture the actual scoring cards in a trick.

After the hands have been exhausted, the first day is concluded. The dealer then distributes the cards for the second day, discarding any leftover cards. After the second day is played, the entire island is scored. Each player looks through their won-cards pile and tallies the point total of the cards captured. If a player captures thirteen or more points of a given suit (i.e., more than half), they score that tribe (essentially, a victory point). All four tribes may not be scored for a particular island, especially in larger games, as the cards may be split evenly enough that no one player scores thirteen points.

After scoring an island, the deal rotates, the cards are shuffled, and the first day of a new island is dealt. Keep playing islands until one player scores five tribes. That player is the winner.